The Italian POW lived in huts at the other end of the cricket pitch (opposite the Craft Centre). The land used to be covered with elderberries, brambles and tree stumps but it was cleared and levelled so they could make a football pitch with goal posts.

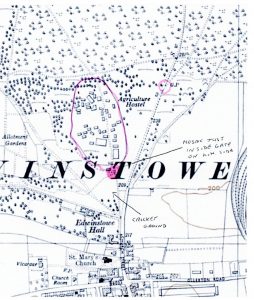

This Mosaic was designed by the Italian prisoners of war and was at the entrance to army / displaced people’s camp in forest. 1946-8. There are no traces of it now but was positioned as on the map.

The UK Coat of Arms

Acknowledgement Wikipedia

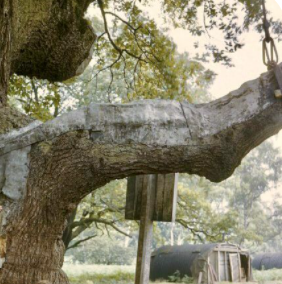

Within the forest and right up to the Major oak there were many ammunition storage huts as shown in the photograph below. Along the paths the footings of the nuts can still be seen.

After the war the Italians returned home and displaced people (migrants) from all over Europe came to the camp. There were Poles, Czechoslovaks, Latvians and Russians. Most of them worked down the pit with the local men. Others worked on farms growing food to help feed us. They knew they could not go home as they would be called collaborators (people who worked with the enemy) as they had been freed in Germany. They were known by many as very good workmen.

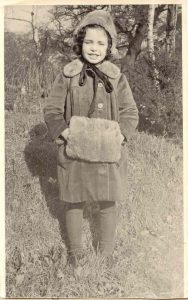

My childhood in Edwinstowe POW camp – 1948

Written by Vera Beljakova, who lived with her parents, Boris and Marianne, and grandfather Alexander Beljakov at the Edwinstowe POW camp for 2 years – 1948-49. Boris B. was the Camp interpreter and liaison officer.

Vera Beljakova is a former Sunday Times, Johannesburg, feature writer.

Few people remember Prisoner-of-War camps with much love or affection, but I do.

It was 1948, I was 4 years old and I arrived at Edwinstowe Camp. Admittedly, by the time my mother brought me and my paternal grandfather from war-ravaged Germany to join my father in Edwinstowe, it was more of an agriculture camp with military security.

It was 1948, I was 4 years old and I arrived at Edwinstowe Camp. Admittedly, by the time my mother brought me and my paternal grandfather from war-ravaged Germany to join my father in Edwinstowe, it was more of an agriculture camp with military security.

The prisoners were East European soldiers as well as former Russian Tzarist officers. They had been sent to Edwinstowe to work in the fields.

My father (Boris Beljakov) was employment at the camp as an interpreter/ translator/liaison-man by the British camp authorities to guard them.

Most had no country to return to after WW2, since their homelands were now Soviet Union territories (Russia). Most were East Europeans and spoke a variety of languages from the Baltic North to Southern Ukraine.

My father spoke most of these languages, including good English so he could talk to them in their own language.

The spell of Sherwood

As I was a young child I did not understand all this but fell under the spell of the forest, right on the doorstep of our prefabricated hut. These huts were by the cricket pitch where many of you play, walk and have fun.

As I was a young child I did not understand all this but fell under the spell of the forest, right on the doorstep of our prefabricated hut. These huts were by the cricket pitch where many of you play, walk and have fun.

For me this was paradise. I loved the major Oak and we visited it each day with my grandpa (Alexander Beljakov) He would walk and I would wildly weaving around in and out of the bushes.

I didn’t have much to do with the “prisoners”, as my food was brought from the canteen to our hut or my mother cooked because some of the communist POWs were nasty and unkind to us and it was unpleasant to be there.

Life in camp

At night the grown-ups played bridge, “skat”, chess, backgammon and other card games, while I was left alone in our hut, with strict instructions not to open the door to anyone, otherwise the Big Bad Wolf of Sherwood Forest would carry me away to his den. I would crawl under the bed to sleep, so that the Big Bad Wolf would not find me if he broke in. I soon realized this was not true.

At night the grown-ups played bridge, “skat”, chess, backgammon and other card games, while I was left alone in our hut, with strict instructions not to open the door to anyone, otherwise the Big Bad Wolf of Sherwood Forest would carry me away to his den. I would crawl under the bed to sleep, so that the Big Bad Wolf would not find me if he broke in. I soon realized this was not true.

Birthday delights

There were many happy times. For example as my 5th birthday I received a tricycle. This gave me a sense of freedom, racing around the camp, trying to copy the military policeman roaring around on their big black motorbikes.

The Military Policeman spoilt me rotten with boiled sweets which I had never seen before coming from Germany where we were starving.

I was adventurous and the Military Police were called many times when I climbed a tree and could not get down again. They were very kind and gave me chocolate. But I was at home I was smacked for my adventures and causing so much trouble.

Education

Time came, when the Village Policeman arrived to inform my Mother that she was breaking the law by keeping me at home and away from Infant School.

She offered to do “Home Teaching” which didn’t go down too well, considering that she couldn’t speak English in the first place (well…just a little to get by), but not enough to educate me into becoming a little English Person.

Next day, under severe duress, she – with me in tow – were marched by the Village Policeman to the Infant School, with my mother weeping all the way – and me bouncing joyfully along, ready for the next adventure called “English School”, which would make a change from climbing trees and getting whacked for it.

“School” was great – I wish I could remember my teacher’s name back in 1948, but on Day One she gave me a black crayon and asked me to colour in a cat’s outline – easy, since being a lonely child, I spent hours entertaining myself with crayons and pencils at home during bad weather.

From there I graduated, under the influence of my eager classmates, to drawings on the corridor walls. My speciality: Robin Hood, Maid Marion & Big Bad Wolf.

Although I seemed to be the only child in the camp, there must have been one or two other camp boys, for they taught me how to throw mud at wet sheets on washing lines – punishment was awesome – I only did it twice….contact with boys was banned.

Back to the forest

When not getting into trouble, I played in Sherwood Forest, acted out in fantasy dramas of being “Maid Marion” and forced Grandpa to pretend he is “Robin Hood” – for an old Russian steel-merchant, born way back in 1875 in Riga, on the Baltic Sea, all this must have been enormously strange, but he indulged me.

A ll I really remember was that it was the happiest time of my life, and I think my parents and grandpa also loved Edwinstowe and Sherwood Forest. Yes, goblin, dwarfs, fairies, elfins, wood nymphs and sprites really did live there in Sherwood Forest – I swear I saw them! Pity that adults couldn’t see them too ……but they had lost the wonders of childhood perceptions.

ll I really remember was that it was the happiest time of my life, and I think my parents and grandpa also loved Edwinstowe and Sherwood Forest. Yes, goblin, dwarfs, fairies, elfins, wood nymphs and sprites really did live there in Sherwood Forest – I swear I saw them! Pity that adults couldn’t see them too ……but they had lost the wonders of childhood perceptions.

Don’t look back in anger

We were very sorry to leave when the camp closed down, and sad-heartedly moved to Mansfield, then Sheffield, later Nottingham.

I have never been back to Edwinstowe but cherish my dear happy memories of the camp and its mysterious forest.

Postscript

Later my parents parted and subsequently my mother married a former POW from Edwinstowe, Alexander Makarovich.

No one in the camp knew at that time that he was from a noble Russian family, fought in WW1, the Russian Revolution, the Russian Civil War as a junior officer and was holder of the St George Cross for Bravery under fire.

His grandfather fought in Napoleonic Wars in Russia in 1812. And then, in one life-time from a nobleman Hussar Officer in the Life Guards to a stateless person and potato digger in the fields of Edwinstowe until he moved to Nottingham and started life all over again : from factory watchman to private tutor to students at Nottingham University.

1948 Edwin Wedding at St Mary’s Church.

Sequel

Later my parents parted and subsequently my mother married a former POW from Edwinstowe, Alexander Makarovich.

No one in the camp knew at that time that he was from a noble Russian family, who fought in WW1, the Russian Revolution, the Russian Civil War as a junior officer and was holder of the St George Cross. His grandfather fought in the Napoleonic Wars in Russia. And then, in one lifetime from a nobleman Hussar Officer in the Life Guards to a stateless person and potato digger in the fields of Edwinstowe….until he moved to Nottingham and started life all over again : from factory watchman to private tutor to students at Nottingham University..

People in the Edwinstowe POW camp story:

Vera Beljakova (born Berlin 1943 – Johannesburg)

Journalist, Editor, PR. (many years with the Sunday Times, Johannesburg)

Father Boris Beljakov (St Petersburg, Russia – 1912 + Bremen 1985 )

Camp Translator, later bookkeeper and shipping-agent

Mother Marianne Beljakov (nee Miller) (Saratow, Russia – 1910 + Nottingham 1974)

Daughter of a judge, born into Russian noblity. Later dress designer.

Grandfather Alexander Beljakov (Riga, Latvia – 1875 + Germany 1952 )

Russian steel-wire merchant

Stepfather Alexander Makarovich (Russia 1899 – Nottingham 1972)

Military family background. Later Land surveyor, teacher & tutor.

More Memories

My wife is a keen Radio Nottingham listener and she told me about the former POW camp item on Breakfast with Karl.

We are both members of St John’s Church in Worksop and last year a 100 year old member died; her name was Dorothy and I used to visit her regularly.

I conducted her funeral service in St John’s and I told the congregation about her long friendship with Werner, who was a former German POW at the Norton Cuckney camp near Edwinstowe.

Just after the war in Europe ended the then vicar of St John’s asked the congregation if anyone would be willing to invite locally based German POWs to Sunday Lunch.

Dorothy said she would and so began what became a lifelong friendship with Werner.

He came every Sunday from then on until he returned to Germany; he walked the 4/5 miles from Norton Cuckney, though later on Dorothy bought him a 2nd hand bicycle which made things a lot easier for him.

After he was repatriated Werner was ordained priest into the Lutheran Church; later he became a Professor of Theology.

I met him on several occasions because he visited Worksop many times and Dorothy visited him in Germany.

Werner would love to have been well enough to make the journey to Worksop to attend Dorothy’s funeral; he is now in his mid eighties and we are still in touch.

Peter Moorhouse

The photos below show the areas where the ammunition huts were.

We are aware that the picture is unclear.

We are aware that the picture is unclear.

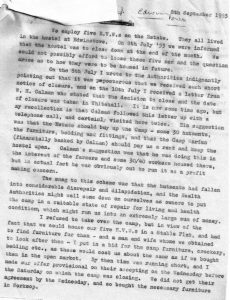

THIS IS A COPY OF A PHOTOGRAPHED LETTER SHOWN TO THE EDWINSTOWE HISTORICAL SOCIETY BY MEMBERS OF THE THORESBY ARCHIVE OFFICE ON A VISIT TO THORESBY ON MONDAY, 11TH FEBRUARY, 2019.

Lord Manvers 8th September, 1953

European Voluntary Workers – E.V.W. Camp, Edwinstowe.

We employ five E.V.W.s on the Estate. They all lived in the hostel at Edwinstowe. On 8th July ’53 we were informed that the hostel was to close down at the end of the month. We could not possibly afford to loose these five men and the question arose as to how they were to be housed in future.

On the 8th July, I wrote to the Authorities indignantly pointing out that it was preposterous that we received such short notice of closure, and on the 10th July, I received a letter from W. H. Calman who stated that the decision to close and the date of closure was taken in Whitehall. It is now some time ago, but my recollection is that Calman followed this letter up with a telephone call, and certainly visited here twice. His suggestion was that the Estate should buy up the Camp – some 30 hutments, the furniture, bedding and fittings, and that the Camp Warden (financially backed by Calman) should pay us a rent and keep the hostel open. Calman’s suggestion was that he was doing this in the interest of the farmers and some 30/40 workers housed there, but in actual fact he was obviously out to run it as a profit-making concern.

The snag to this scheme was that the hutments had fallen into considerable disrepair and dilapidation, and the Health Authorities might well come down on ourselves as owners to put the camp in a suitable state of repair for living and health conditions, which might run us into an extremely large sum of money.

I refused to take over the camp, but in view of the fact that we could house our five E.V.W.s in a Stable Flat, and had to find furniture for them – and a man and wife whome we obtained to look after them – I put in a bid for the camp furniture, bedding etc., as these would cost us about the same as if we brought them in the open market. By then time was running short, and I made our offer provisional on their accepting on the Wednesday before the Saturday on which the camp was closing. We did not get their agreement by the Wednesday, and so bought the necessary furniture in Worksop.

During his conversations Calman stated that he had been working with the Authorities responsible for the camp, and offered to speak to persons in charge of the camp and its equipment, in Nottingham. This he did, and one of them (Mr. Spendlove) came over here and discussed matters with me. When the deal for buying the furniture etc. fell through, an end was put to Calman’s project of profit making there. He then turned nasty and sent a bill for £4.4.0 “for interviewing Authorities in Nottingham as per my instructions”. As I said before, there was no question of our engaging him professionally, and in actual fact he was really working in, what he hoped to be, his own interests.

I relied to Calman that I had not engaged him professionally and he then wrote to you. I suggest that you reply to him as follows.

Edwinstowe Historical Society

Edwinstowe Historical Society