Christopher Thomson was born at Hull, on Christmas day, 1799. His father was a sailor. ‘He received his education at the Free School of Sculcoates, Hull.

In 1810, Christopher’s father gave up his sea faring life and opened a public-house the ‘Ship’. Christopher was witness to many scenes of drunkenness.

In 1813, he was bound to Messrs. Barnes, Dykes, and King, ship builders, under the Cogan’s Charity of Hull. They provided evening school for the boys, which Christopher gladly attended.

His father subscribed to a circulating library for his son and Christopher made acquaintance with the works of Milton, Shakespeare, Sterne, Johnson, and several other authors, besides reading many volumes of prose fiction.

When about seventeen, he paid his first visit to the theatre, and saw “King John” performed – to act himself was now his sole desire.

When his apprenticeship was complete, he was engaged as carpenter’s mate in a whaling vessel, and made a voyage to the Greenland seas.

In 1821, he was married to Miss Hannah Leaf, the daughter of a veneer sawyer, under whom he took employment. Shortly afterwards, due to mechanisation, he and many of his work mates were unemployed and became poverty-stricken.

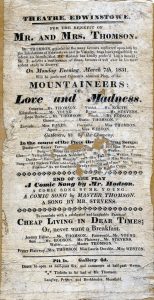

Leaving his employment as a veneer-sawyer, Christopher became an actor and joined a company of strolling players.

Many were the hardships and trials which Christopher and his wife underwent during their ten years of strolling life.

Sometimes Christopher was obliged to turn his hand to ” painting transparent window-blinds, making painted glass boxes, chimney ornaments, and such like nick-nackeries,” to keep starvation from his door.

At one time Christopher opened a school in the village of Tickhill but because he refused to beat the boys when they could not ‘say their spelling,’ they became saucy, and overbearing and his school having failed, he resumed his strolling life.

In 1828, they travelled from Arnold, to Blidworth looking for lodgings under the dark-hooded night, with bleeding feet, penniless and supperless? Life was hard.

Christopher then found himself in Edwinstowe and the villagers supported him in starting a business as a house-painter.

His cottage was just over the River Maun bridge on the right. A friend recorded,

“We found the walls of his parlour covered all over with the works of his easel; in little niches, on each side the fire-place, were busts of the poets, placed over goodly rows of books.”

Christopher stated, “It was my privilege, soon after settling in this village, to make the acquaintance of two or three right thinking men and thus early we pledged ourselves mutually to endeavour to banish crime from the village, and if possible, restore it to virtue and freedom.” His great desire was books.

He did more and he and a group of likeminded people set up the library for the benefit of working men. On discovering that few could read he started night classes in 1838 in the Jug and Glass.

The Edwinstowe Artisans Library and Mutual Instruction Society charged a penny -1d- entrance fee and ran three nights a week. It was open to both men and women. Classes were free but members provided their own coal, candles and books. Instruction was offered in reading, writing, arithmetic, music, drawing and conversation.

An annual ball was held to raise funds and after nine years they had five hundred volumes of books.

An annual ball was held to raise funds and after nine years they had five hundred volumes of books.

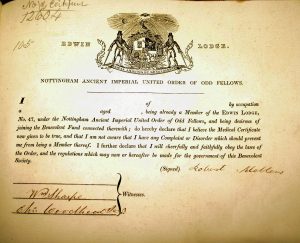

A branch of the Odd-Fellows had been established in Edwinstowe and in 1833 Christopher joined it. He often acted as Secretary and helped found 40-50 other lodges. He believed in “self-help” and encouraged others in the village to lay up sums of money aside in case misfortune assailed them. The “Association of Self-Help ” was formed among the artisans in 1847.

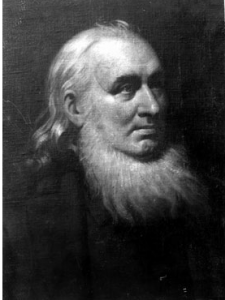

In 1847 this is how his friends described him,

“We found him at work in his garden, and directly he saw us enter the gate, he dashed his spade into the ground, and came forward with his hearty right hand, to welcome us. He is a man of middle age—somewhere between forty and sixty; for it is difficult to tell his age by his looks, he is so hale and strong. He has a fine face, which would look well in a picture. His cheeks are stained with the fire of the morning; his eyes are bright and intelligent; his hair long, and streams over his shoulders, like the white locks of one of Ossian’s storm-heroes. He is English to the back-bone, and has done and suffered much in his time.”

“We found him at work in his garden, and directly he saw us enter the gate, he dashed his spade into the ground, and came forward with his hearty right hand, to welcome us. He is a man of middle age—somewhere between forty and sixty; for it is difficult to tell his age by his looks, he is so hale and strong. He has a fine face, which would look well in a picture. His cheeks are stained with the fire of the morning; his eyes are bright and intelligent; his hair long, and streams over his shoulders, like the white locks of one of Ossian’s storm-heroes. He is English to the back-bone, and has done and suffered much in his time.”

His family had now increased to seven—three boys and four girls, alive. They were all children of promise, possessing talents. One was a poet and many were singers and musicians. Life was good.

His trade was very dependent on making improvements in Rufford Abbey, by the Earl of Scarborough but when the Earl had large tax bills Christopher’s employment was reduced.

Rufford Abbey rooms possibly decorated by C Thomson – building now demolished

Shortly afterwards Christopher and his large family left Edwinstowe and settled in Sheffield working as a newsagent. His new business was unsuccessful as he was far too liberal in giving credit. It was at this time that he stated, “I have a most kind, indulgent, and industrious wife, and to her I owe my happiness.”

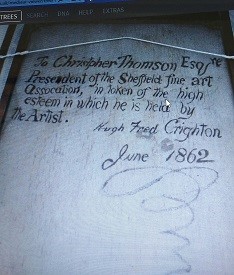

Then in 1854, he turned his attention to landscape art and in the following year, 1855 he assumed the profession of landscape-painter.

Then in 1854, he turned his attention to landscape art and in the following year, 1855 he assumed the profession of landscape-painter.

He visited the Royal Academies and other exhibitions and with the generous support from his friends he succeeded as an artist.

His art work can be seen in Sheffield art gallery.

In later years, the Night Classes and Library moved to the ‘Old Library’ (built in 1913) and followed in a similar tradition.

The link below to view the Blue Plaque:

Edwinstowe Historical Society

Edwinstowe Historical Society