An advertisement in a 1928 newspaper read:

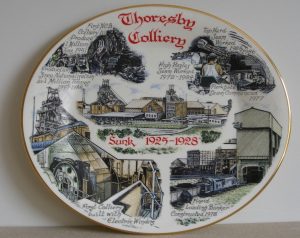

Thoresby Colliery, ‘a pit set amongst the silver birches’

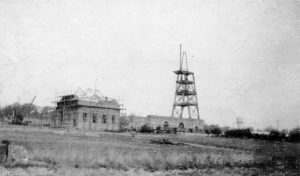

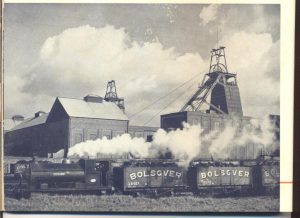

Located in the heart of Sherwood Forest, Thoresby Colliery was the last Nottinghamshire colliery to be sunk by the former Bolsover Colliery Company between 1925-28.

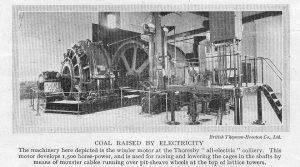

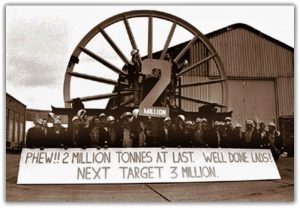

It was the first pit in the country to be built with electric winding. The first pit without a chimney. In 1951, Thoresby became the first nationalised mine to exceed a million tons output in one year. One of the most productive and profitable coal mines in Europe for many years, in 1988 went on to produce two million tons in 43 working weeks.

During the early 1980s, Thoresby had a workforce of almost 1,500 men with the majority living in Edwinstowe, by 1994, the colliery workforce had reduced to 850, by 2008 just 40 out of a workforce of 500 had an Edwinstowe post code.

Friday July 10 2015, Thoresby was the last mine to be closed in the Nottinghamshire coalfield. The end of an era for the coal mine sunk amongst the birches of Sherwood Forest, known as a record breaking ‘Jewel in the Crown’.

Construction of Thoresby Colliery surface – 1923

Margaret Woodhead has provided the following account: Peer and Pitman

On March 13th, 1896, an article appeared in the Retford & Gainsborough Times, announcing the coming of the East to West Railway from Chesterfield to Lincoln. This railway was built in preparation for the opening up of the Nottinghamshire Coalfield now that the technology was capable of reaching the greater depth necessary. The train quickly became a tourist line to the Forest and was called the Dukeries Line. On the first bank holiday 4,000 tickets had been sold.

Whilst other Lords began to sink new mines, Earl Manvers objected to having a great smoking chimney near his estate.

Why the change of heart? It was because Bolsover Colliery Company was going to sink the first all-electric mine. No smoking chimneys!

By Oct 23, the site of the houses was a problem. After much discussion, it was finally agreed that the site would take land from two farms, Mr Herbert’s at Manor Farm and Mr Greenfield’s at Villa Real which is nearly a mile from the colliery site. Choosing a site for the railway link was to be even more problematic. There would be two mines, Ollerton & Thoresby, within 3 miles of each other and both L.N.E.R & L.M.S had presented bills to Parliament for new lines to them. When these plans were published there was a public outcry. L.M.S proposed to run a line between the two collieries through Beech Tree Avenue.

The Times, Jan 25: Beech Ave consists of 4 parallel lines of well-grown beech trees half a mile in length, and forms probably the most remarkable and beautiful beeches in England.. Ollerton Corner is a well-known rendezvous for hundreds of thousands of visitors who go every year to Sherwood Forest. An immense open space, it is covered with gorse and bracken – the playground of the Dukeries.

Both Earl Manvers and Lord Savile organised a petition against it. Parliament sent both parties back to discuss a merger and a less destructive scheme. A compromise was reached by each mine being connected separately to the existing main line.

Down in the Forest – Coal Reached at Thoresby Pit

The following information is taken from a number of newspaper reports, in the late 1920’s and in 1930.

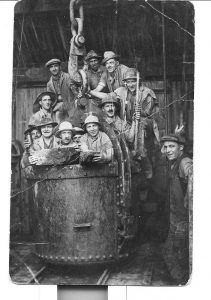

Coal has been won at the Bolsover Company’s, Thoresby Colliery in Sherwood Forest, after a sinking of two years. The sinking was delayed by a strike, a long-drawn-out dispute, and, instead of the sinking commencing in June 1927, it did not start until October 1927. The top hard coal was reached on April 25, 1928.The sinkers had to encounter an unusually large volume of water but, thanks to the cementation process, carried out by the Francois Company of Doncaster, the flow to be dealt with by the pumps never exceeded 900 gallons per day.

The colliery is on the outskirts of the old village of Edwinstowe and is within a mile of the Major Oak. The colliery will, when fully developed, provide work for at least 2,500 men. The most up-to-date methods are to be used; electrical power will be used throughout; the current being carried from the company’s other pits by an overhead line so that chimneys and smoke will not disfigure the landscape.

Edward Hart 4th from left sinking Thoresby Pit in Edwinstowe

Pit Sinkers’ Terrible Fate

Momentary Lapse by Engine Winder. Jury absolve him from blame and sympathise.

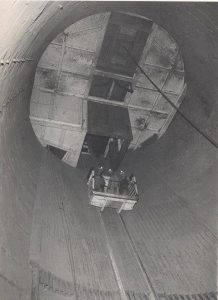

A newspaper report, October 12, 1928, tells of a lamentable accident, involving the deaths of two sinkers at No 2 shaft of the new Thoresby pit. Frederick Brearley aged 40 and Clement Banham aged 33 were killed when they were struck by a descending hoppit which crashed through the doors of scaffolding fixed in the shaft.

The full responsibility for what had happened was taken by the colliery engine-winder himself, who has never before had an accident. “In a moment of forgetfulness, I took my eye off the indicator,” he sorrowfully confessed. After the verdict of the jury, the witness was exonerated from blame and remarkable tributes were paid to winding-enginemen generally.

Joe Bennett recalls:

I can recall several occasions when Peafield Lane and the Rat Hole at Clipstone were blocked by piles of drifting snow and what should have been a short drive took much longer, as the ambulance had to be dug out of the snowdrifts.

Living in a mining village, even as a young child, you were always aware of the dangers at the pit. I would be 7 or 8 years old when Mr. Whitworth, who lived next door but one to us, was killed. He was a banksman, and he died instantly when he was hit by the pit cage.

In the 1920’s and 1930’s, if a fatal accident occurred, all the workmen knocked off and went home, as a mark of respect, the only people remaining on duty being those concerned with safety. On the following pay day, a levy was deducted from the wages of all the workmen, and given to the family of the victim. A typical contribution was half a crown for men – twelve and a half pence in decimal currency- and half of that for the lads. At the time, Thoresby Colliery employed between 1500 and 1800 workmen. It was the time of the Depression and the demand for coal worldwide was low and, often, the pit would only work two or three shifts a week.

I can remember twenty-five fatal accidents and, without doubt, I may have missed a considerable number. Some of whom died in horrific circumstances.

Acorn newspaper

The first one hundred houses were built by the end of 1926, with ninety-two occupied. In 1928 a second phase of building of two hundred and ninety-seven houses was ready for setting on more men when the colliery went into full production in Sept, 1929. There was a temporary school in an army hut bought from Clipstone camp.

You may be wondering, why only two hundred and ninety seven houses? It was 1926 – The year of the great strike. There was a depression, especially in the coal industry, as cheap coal flooded in from the continent. Coal owners met, and they decided on a quota system. Each owner was allowed so many tons of coal per week. This meant every mine working for two days or three per week. For the rest the miners drew dole money. In spite of that, the company did not cut back on the quality of the buildings, only the size of the village. The school was now to be the edge of the site, not its centre, there was to be no swimming pool and no church or chapel, but there was the bowling green, the sports field and the pavilion.

By 1928, Mansfield Road needed widening as far as Warsop Windmill for the increase in traffic. There was still no bus route through to Mansfield, as travel was by train or by carter.

When the miners and their wives arrived in Edwinstowe they came from all over the country- Northumberland, Durham, Yorkshire, Derbyshire, Staffordshire, Wales, Scotland, and also from local pits. Most of the Edwinstowe villagers were not welcoming. They were fearful that the village would be changed beyond recognition and, of course, they were right. The various dialects sounded totally foreign and the peace of this estate village was shattered. Although they were used to being invaded by the tourists, this was different. These people were here to stay, an unknown quantity. It was also not easy for the miners’ wives, leaving behind families and friends and coming to live amongst strangers. The houses, however, must have seemed like palaces, with an indoor toilet, and a bathroom with hot water on tap. These were luxuries their parents did not have. However, Earl Manvers still ruled from the grave. He had died in 1926, and had decreed that there were to be no dogs because of the hunting in the forest. The Bolsover Colliery Company also had a rule that gardens must be looked after or the house and the job were both lost. The Miners’ Institute was run by a Social Committee and they had twenty-four rules. The number of pints of beer per night was rationed to cut down on drunkenness. The Welfare Hall opened in 1936. This was where Girls’ and Boys’ Brigades met, the Male Voice Choir and St. John Ambulance members practised and, every Saturday night there was a whist drive and dance for all ages. It was this Committee which had the idea of hiring a train and taking wives and children to Skegness for the day. It was the highlight of the year, an idea which others copied.

Cecil Day Lewis wrote this in his Autobiography, When my father moved to Edwinstowe, it was a country village. Before he died, it had become a mining town…We lived on coal. Seams of it lay below our feet- rich seams which had hardly been tapped yet, for the North Notts Coalfield was the youngest in the country; and my father’s stipend of £600 a year came largely, I believe, from the titled patron of the living, beneath whose land the coal had been found. Had I possessed any historical sense, I could have observed during our years at Edwinstowe a little replica of the Industrial Revolution being constructed before my eyes.

Ref. The Manvers Papers , Nottingham University Archives, Parish Council Minutes, Nottingham Archive Office, Southwell Rural District Minutes N A O Edwinstowe Historical Society Archives, Coal Archives Office, Cecil Day Lewis, The Buried Day (London 1960) p130

Bolsover Colliery Company Quarterly News 1946:

A-B Meco-Moore Cutter Loader

It was in the early days of the late War that the chief officials of the Company came to the conclusion that some drastic efforts must be made to overcome the loss of production which appeared imminent owing to the reduction of the labour force in the mines due to the recruitment of men for the fighting services. After considering a number of possibilities, it was decided that an attempt should be made to cut and load coal simultaneously by mechanical means.

Only one machine intended for such an operation on Longwall Faces was known and its past history – at that time- was not encouraging. Mr. Young and Mr. Sansom immediately entered into negotiations with the makers of the machine.

An old machine was procured and experimental work was put in hand at once. It was agreed that the cost of these experiments should be borne by the Bolsover Colliery Company, Limited and the Mining Engineering Company, Limited. At a later stage, the Ministry of Fuel and Power agreed to sponsor this work and to bear the cost of the necessary equipment.

The Directors of the company, agreed to bear the not inconsiderable costs of all the experimental work at the collieries. After many set-backs a workable machine was evolved and the result is the A.B. Meco-Moore Cutter Loader.

That the machine has proved to be such a huge success is evident by the fact that at the end of August 1946, the machines in operation at the Company’s Collieries, had produced more than one million tons of coal and that at least 250,000 tons of this production was a gain on what would have been possible with the same labour force on the same faces by hand filling methods. It is also a proud fact that in the production of this million tons, only one serious accident to a workman has occurred: a phenomenal achievement.

The photograph above show the teams from Thoresby who were part of the operation.

Clothing Coupons

It would seem that, during the wartime clothes rationing, certain procedures were in place to replace clothing that was irreparably damaged by accident while at work. Here are some extracts;

A letter from a workman, who was thrown from the train and run over while taking the men to work:

As a result of my accident (compound fracture of right arm) I now find myself minus a pit shirt and vest. These garments had to be removed by the hospital attendants and, owing to the damage they did to them and the condition they were in, with blood, they destroyed them. I have no coupons to replace these garments and would be much obliged if you could grant me eight clothing coupons.

From the Board of Trade, London:

In reply to your letter of Jan 30, 1945, I am directed to send to you copies of the application form for the replacement of a worker’s clothing irreparably damaged by accident resulting from his job.

Note: It should be clearly understood that claims under the Industrial Accident Scheme should be submitted only when the garments are claimed to have been destroyed. Those merely damaged and therefore reparable do not come within the scope of the scheme. Nor will replacement coupons be issued in cases where the destruction was due in any way to lack of care on the part of the employee in taking proper precautions to protect his clothing. IMPORTANT. In view of the fact that the 24 coupons from the 1945/46 Clothing Book will have to last for 8 months instead of 6, employers are asked to remind their workers by circular or poster that it is more important than ever before to take every possible precaution against industrial accidents to their existing clothing, and to warn them that while supplies are so short replacement of damaged clothing may have to be made on a reduced scale.

I am pleased to say that the workman got his coupons!

Acorn newspaper

Thoresby War Service – War Service Fund

This fund was commenced at the outbreak of war, when every workman contributed 3d in the £ from his wages. During 1943, a total of £4,695 was paid out, £3,808 being paid out to the dependants of serving employees, £757 to sons and daughters, and £130 to hospitals and family doctors. At the present time, there are 114 employees in service, 58 married, 5 with widowed mothers and 51 single. There are 56 children of employees, as well as, 162 sons and daughters in receipt of benefits.

Four employees have been killed on service: J. White 1940, Geoffrey Lacey 1943, G. Askew 1944 and G. Woodcock 1943. Four employees are prisoners of war: Sgt. A. Wagstaff, Pte. F.G. Mellors, Pte F Vernon and Pte. G.W. Rowney. Of the sons and daughters of employees, four have been killed on service: A Mendham, C. Burrows, O.W. Woodhead and R. Portman. Three are reported missing: Ralph Richardson, Jack Foy and C.R. Faulkner, and Jack Jones died on service in India. There are two prisoners of war: C.W.H. Winter and J. Cornish. The fund is managed by a committee, with Mr. Woodward as Chairman, and Messrs. R. Hill, T. Ogden, C. Coldbeck and B. Evans, Mr H. Willett, Secretary and Mr W.H. Russon Treasurer.

Bolsover Colliery Company News 1944

Winding Rope Incident

Dangerous incident

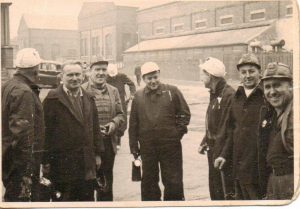

In November, 1951, a group of Turkish journalists was visiting the country as guests of the Foreign Office. During a visit to Thoresby Colliery a winding rope broke in No 1 downcast shaft.

The cage crashed through the baulks into the sump. No one was injured and production was not hindered. The men were brought to the surface later by No 2 shaft. The photograph shows Harry Fletcher and Bernard Evans, Secretary and President of the N.U.M, with the journalists. The photo is possibly unique, for in the background is shown where the cable broke.

October 1947 Lord Field Marshall Montgomery visits Thoresby Colliery

Alf Bonsor, Lord Montgomery, Bernard Evans

Alf Bonsor, Lord Montgomery, Bernard Evans

It was Lord Montgomery’s first visit to Nottinghamshire, the Notts pits were selected for a visit because of their magnificent records in coal production.

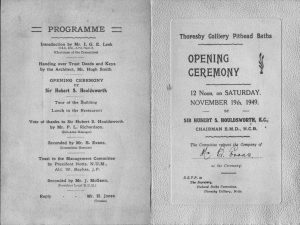

Thoresby Colliery Pithead Baths Opening Programme Plan 19th Nov

1949

New Pithead Baths

In November 1949, Sir Hubert Houldsworth, the then Chairman of the East Midlands Division of the N.C.B opened the new Pithead Baths. This meant that the workmen would not be leaving the colliery in their ‘pit muck’, a term used at the time. They could leave their work clothes in a locker. 1,584 clean lockers and 1584 pit lockers were provided. 54 shower cubicles and an ambulance treatment room were all provided on site. The workmen could have a shower and go home in clean clothes. For a while a number of men could still be seen leaving the pit with blackened faces; they would not use the new facilities and continued to go home for a bath.

Coal News Article 1951

In the August 1951 edition of the Coal News, Sid Chaplin wrote of his visit to Thoresby Colliery. Thoresby Colliery is now reaping the benefits of reorganisation. They’ve recently installed 10½-ton capacity skips in the shaft and, since 1946, they’ve driven five miles of roadway through the main solid. The result has been a big saving in manpower – between each of the two loading points and the screens there are only five men. They have nine Meco-Moores operating; 80 per cent is power-loaded. Output has gone up 50 per cent on last year. I asked Manager Sam Thorneycroft how they had done it. ”Reorganisation,” was the reply, “plus men who have used reorganisation to the best advantage: they are the most versatile workmen I’ve ever met. They’ll tackle any job in the pit. And they take pride in their work.”

Edwinstowe the village attached to Thoresby, is pleasant and friendly. Engineer Tom Haynes, who has worked at many collieries, declares that Edwinstowe is, “the nicest village I’ve struck yet.”

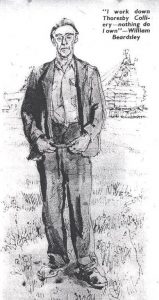

In the Institute, I had the good fortune to meet the first two men to start as coal-getters at Thoresby. “It’s 24 years since we started,” Bill Beardsley told me. “The first two men to put a pick into Thoresby coal.”

His mate was Ernest Gannon, who now drives an underground winder. Bill lost an eye and is now a datal man, which inspired the following poem:

I’m only a poor old dataller,*

No place to call my own,

I work down Thoresby Colliery

Nothing do I own.

I pull off my shirt and trousers,

Work as hard as any man;

My name is William Beardsley,

You all know who I am.

And everybody does know William Beardsley, though mostly it’s “Fisherman Bill,” a proper designation for a man who declares, “I’ll fish to the finish!” Talking to Ernest and Bill, and later to Bernard Evans, N.U.M Branch President, and Jack Riley, who helped to drive most of the five miles of new roadway at Thoresby, I found that all had one thing in common: pride in their pit, pride in their village.

(*Dataller, a workman given various jobs around the pit)

The sketch of Bill Beardsley was by H.A Freeth.

Thoresby Memories

Vernon Staley, left Edwinstowe Council School just before his 14th birthday and went to work underground at Thoresby Colliery with no training. It was expected that a young miner would acquire the knowledge that he needed in his job through first-hand experience.

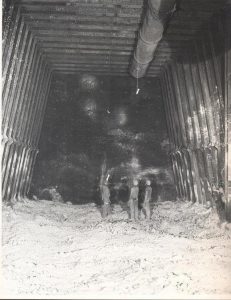

It was 1935 and Thoresby was working a five-day week. One Friday, he was asked by Alex Wood, underground head surveyor, to take readings of the air circulation at the coal face. The lucrative Tophard seam had just been discovered and it was essential that the seam could be developed in perfect safety. Vernon was equipped with an anemometer, raw plugs, a raw plug tool, a hammer and extension string, the tools of his trade. One Friday he was returning to the pit bottom, via the 4’s seam, when he heard a gurgling sound, followed by a muffled roar. Vernon ignored a golden rule of the mining industry: “Thou shalt not run in a coal mine!”, and raced towards the underground office at the bottom of the shaft. Vernon continues: “Bill Ward, the senior overman, curbed my speed. When I explained my haste he immediately picked up his stick, his hand lamp and his oil lamp and hurried to the 4’s face with me in tow. We passed through several air-lock doors before we heard an unmistakable gurgling sound, followed by a roar. Bill never batted an eyelid as a wave of water rolled over our boots. As I watched Bill’s reaction I wondered whether we should retreat. Remember, I was only 14 years old. The rush of water was caused by the extractor fan on the surface which was designed to remove the impure air from the coal seams and replace it with fresh air. The fan motor had strength of 250 HP and it was this power that was creating a vacuum that had moved thousands of gallons of water and made all the noise. By Monday, the water had subsided”.

Mining was a reserved occupation during World War 2 and Vernon was then employed as an underground electrician. He reminisces: “In 1940, I contracted conjunctivitis and had to come out of the pit. Here was my chance to join my pals in the forces. I enlisted in the R.A.F. in the Nottingham recruitment office and was approved for aircrew but, within a short time, I was recalled and interviewed by three R.A.F. officers. There was a shortage of tradesmen and I could serve as an electrician or return to Thoresby Colliery.”. Vernon chose the R.A.F. and, after completing a course of training at Henlow, Bedfordshire, he was posted to India and Burma. The allied forces were forced to retreat from Burma and Vernon’s next posting was to various stations in the Pacific.

He concludes: “After four years’ service I was demobbed and, in due course, arrived back at my parents’ house on First Avenue just in time for tea”.

Acorn newspaper

Pit Top 1950’s Charlie Ringham, Bernard Evans, Sam Thorneycroft Colliery Manager

BBC Archive Reconstruction at Thoresby Colliery – Monday, 7 January 1957

https://bbcrewind.co.uk/asset/600eaf053a53aa00278ecd19?q=edwinstowe

Malcolm Chapman, started work at Thoresby when he was 17 ½. He worked on the screens until he completed his underground training at Crown Farm, then he worked at the coal face in development. When the first bunker was built at 51’s loader, he worked with Walt Mellors, Derek Green, Jack Hallam and Jock Cramm.

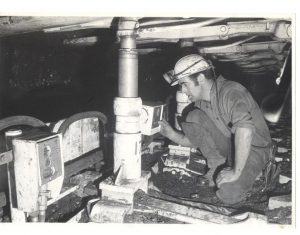

He is pictured with Billy Coxford and John Cotterill during the installation of the 1,000-ton vertical bunker. Malcolm said “There were five underground bunkers altogether capable of holding about 4,500 tons of coal and they were all built using a different technique. It was practice to use outside firms to install the bunkers, but Mr Wheatley, the Colliery Manager at the time, said that the workforce at Thoresby was quite capable of doing the job. It was surprising how quickly the job was done. Before sinking, 6ft circular tubbing was put into place and then it was filled round with concrete and this formed the top of the bunker. I remember it took about a week to fill with concrete. We were all on 12-hour shifts and we got extra pay because it was shaft work. We all made a bob-or-two.”

His wife, Josie, recalls that the children never saw their dad when he was on 12-hour shifts. She said, “I used to remind them who he was!”

Acorn newspaper

Oil seepage at Thoresby was causing great problems and between January and May 1967, BP recovered around 150 tons. To carry the oil out of the pit it was collected in a number of small converted mine cars, and held in a special 12,000 gallons capacity tank installed by BP. The tank situated underground, collected the crude oil found in the workings from the Bothamsall field. The oil belonged to British Petroleum.

Ken Tucker and Richard Kirkland remember the incident very well. They were employed at the time as part of a salvage team recovering cables and equipment. Richard said, ‘The smell was very offensive, it never left you, and you could even smell it when you got home.

Ken remembers being supplied with new boots and clothes every day. He said that they had to be burned when they had finished their shift.

Richard said, ‘Whilst the oil was down the pit where it was warm, the oil was in liquid form, but when it was transported to the pit top, particularly when it was cold, it solidified and to get it out of the mine cars the surface lads had to light fires under them’

During 1969, there was a serious underground heating. The fire got out of hand and the whole of the south side Top Hard working had to be abandoned with the sealing off of two panels, seriously affecting production. After a number of years the district was re-entered.

by Fred Sperrik

https://bbcrewind.co.uk/asset/6064612f8b30bf001fcf650a?q=edwinstowe

A new electric winder, replacing the original electric winder, was installed at No 1 shaft during the two weeks’ holiday period. The winding house roof was removed and the 120-ton winder drum had to be hoisted by crane into position. No 2-shaft replacement was completed in 1981.

A new rapid-loading bunker was commissioned in 1978 and a £4.7m refurbishment scheme included a new covered walkway from the pithead baths to the pit top, new office accommodation, a lamp room and other surface buildings.

Big Mike, Dick Gillott, Tommy Derby, ? Brian Dickenson

A 1,000-ton vertical underground bunker was installed in 1978 and a 1,000-ton inclined bunker was completed in 1983 – See photos

BBC Archive News from 1984

https://bbcrewind.co.uk/asset/606c4867c147f4001f814c45?q=edwinstowe

Water Tower – note forest in background Water Tower 2015

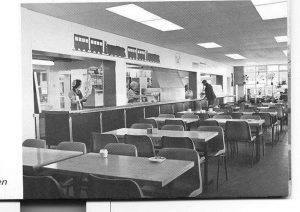

Thoresby Colliery Canteen

Thoresby Memories – The Ladies of the Canteen

“I enjoyed every minute that I worked in the canteen. We had loads of laughs and, even though there were 15 women working together, we all got on really well.”

These were the words of June Burgess. June was the Control Clerk for nine years and she was the Canteen Manageress for two years. In 1979, June remembers going to the Winter Gardens in Blackpool for the “Canteen of the Year” finals. They carried off the title, defeating fifteen other Coal Board areas in Britain. Irene Burridge was the Manageress at the time, and Moira Sheppard her assistant. The team, representing 15 ladies who worked on the two shifts at the pit, had to spot the mistakes relating to hygiene and safety in a special mock-up kitchen. June has kept the photos, the programme, and all of the newspaper reports in an album.

She recalls, “Monday mornings in the staff room, where you could always keep up-to-date with the local gossip; Thursday mornings, going over the ‘the hatched’, ‘matched’ and ‘dispatched’ in the ‘Chad’. Nothing was ever missed. Everyone was kept busy, and there was a constant stream of workmen passing through, with hot meals being served all day, but we all worked together and got on with the job.”

Joan Linford, Beryl Hayden, ? Margaret Froggatt, Annie Cowie, Irene Burridge, Lottie Froggatt, June Burgess, Violet Lynn, Beryl Doyle, Ivy Thorburn, Phyllis Brown.

Jane Chapman was eighteen when she started working in the canteen and she remained there for fifteen years. Her first job was on the tea bar and she remembers, “The tea pots were enormous and very heavy, and there seemed to be a never ending queue of workmen, and we often ran out of cups. As well as drinks we also sold crisps, sweets, chewing tobacco, snuff, and chewing gum, ‘Beechnut’ was the favourite.”

When Jane was on days she got up at 3.30a.m, the van driver often had to knock her up, and she always fell asleep in the van as it continued on its round, picking up the other ladies.

Once at the pit, they only had half an hour to get the canteen up and running in time for the day shift. There would also be list of men who qualified for a free meal for staying overtime on the night shift. They were kept very busy until it began to ease off around seven.

The canteen was split into two sides, the clean side and the dirty side, and woe betide any workman who sat down in the clean side with his dirty pit clothes on! During the day the canteen floor was swept, mopped and scrubbed in between shifts, with the chairs and tables being moved from one side of the room to the other. Vegetables were delivered three times a week and were all prepared by hand, except for the potatoes, which were put into a rumbling machine. Jane said, “You needed plenty of strength to lift the containers full of potatoes onto the stove, it would probably be against Health & Safety regulations now”

“The afternoon shift started at 2pm and didn’t finish until 11p.m, by which time you were really tired, but you still had to cash up, empty the shelves in the tea bar and stack all of the chairs on to the tables”.

She remembers when one of the girls got married, they formed a guard of honour outside the church with a row of mops. Even though it was hard work, Jane enjoyed her time at Thoresby, and would have continued to work there, but they all had to leave when the pit was privatised, although a few of the staff did get transferred to other canteens.

Froggatt’s Canteen

Little wonder that the canteen was often referred to as ‘Froggatt’s Canteen’.

Margaret Froggatt started work in the canteen in 1959, her sister Iris already being employed there.

Margaret was employed for twenty-eight years, and during that time was joined by a number of family members, including her mother, her sister Mary, her sister-in-law, Lottie, Lottie’s daughter-in-law Jean, and Lottie’s daughter, Maureen.

Margaret’s first duties were in the kitchen, washing the pots and preparing the vegetables. Mrs. Shepperd was the canteen manageress at the time. After a number of years, and other duties, she became cook. Margaret remembers that, in addition to breakfasts and dinners, the Cornish pasties, puddings and the renowned egg custards (The workmen would often take them home for the family) were made fresh every day.

She also had the job of steaming six hams every week for the cobs and sandwiches that were sold on the snack bar.

In addition to their daily duties, the canteen staff had to prepare buffets for V.I.P’s visiting the Colliery, Margaret said, “Often this would include cooking a whole salmon”. For a number of years the ladies provided the meals for the Meals on Wheels Service in the district.

The canteen inspectors would arrive unannounced to check the canteen and the cutlery, and the Canteen Manageress was always very keen to have the highest standards of hygiene in the canteen.

Lottie remembers that when there was an accident or incident at the pit they often worked through the night, providing drinks and meals for the workmen involved.

Christmas was always a busy time. Lottie recalls the staff taking turns in having a stir of the Christmas puddings. They were mixed in a special dustbin because of the large quantity needed so that all of the workmen could have a Christmas dinner.

Lottie said, “For many years they also provided the food that was served at the Retired Miners Party held in the Welfare Hall. This was prepared after they had finished their daily shift. It was often the early hours of the morning before they had finished.”

Over the years the staff was involved with many fund-raising activities for worthy causes and, during the bread strike, the canteen was turned into a bakery, providing bread for many of the other canteens in the area.

May Condon, ? Lottie Froggatt, Beryl Hayden, Joan Linford, Phillis Brown, Margaret Froggatt, Irene Burridge.

It is obvious that, even though the ladies of the canteen all worked very hard, they all enjoyed working at Thoresby. They enjoyed the fun and the banter with the workmen and all stressed how they were always treated with the greatest respect and that their hard work was appreciated by the men who worked at Thoresby.

In At The Deep End

Starting at Thoresby Pit Canteen in 1978, Jean Mendham worked alongside the other women behind the counter, serving quality meals round the clock to the miners. Jean started on the breakfast shift with Mary Bamford, then later with her daughter, Joy. Having to wake at 3.30a.m, with a cup of tea from her husband, she was driven in a van, by Keith Gozzard, to pick up the other ladies, often calling at Ollerton and Warsop. Clocking on for 5.a.m, Jean and Mary warmed up the cookers ready for the day shift at 5 30 a.m. Even thought there were only two ladies behind the counter for breakfasts, they still managed to serve a full breakfast to hundreds of workmen.

Alongside this, the place constantly needed to be cleaned, ready for the next wave arriving to be fed. Regardless of the constant hard work, Jean remembers how she loved every minute of it, mainly because of what a great team the ladies in the canteen were, and how rewarding the work was at the end of the day.

“It was known as Froggatt’s Canteen at one point because five of them worked with us at the same time” says Jean. “We were all friends and helped each other out, we shared our troubles and all got on so well together”.

They often provided catering if ever anyone was having a wedding or was in need of a buffet for an occasion. Fridays at the canteen became a focal point for socialising, with Fred Scully coming in for the Tote and retired miners, sometimes with their wives, arriving for a lunch and to reminisce on old times. Jean remembers specifically the strike.

Going in to feed those who continued working, “It was awful going up the Pit Lane, such a worrying time. The standard at the pit canteen was part of the ladies’ pride and joy. Cleanliness and hygiene were always top of the agenda and, proudly there was not one case of food poisoning ever reported from the canteen’s food. “Meat pie and fish and chips were always a favourite with the lads, but puddings, too! We always had fresh custard and, even though we were only supposed to put on a spoonful, they always said, “Put us a bit more on, lass.”

Christmas was always a busy time.

We prepared and cooked fresh Christmas dinners for every shift so, whenever we had a spare minute, we’d be peeling sprouts and chopping spuds”

Jean says, “I would to have stayed on in the canteen. I never wanted to give it up, even though I must have been about 58 at the time, but my husband was not in good health, so I finished”. Jean has fond memories of an organization that was at the heart of the mining community of Edwinstowe and will be remembered for years to come.

“Soon be time for a cuppa lasses”

The Canteen Staff raising funds for the Blue Peter Appeal 1984/85

Ivy Thorburn, June Burgess, Annie Cowie, Jane Chapman, Jane Bradavich, Lesley Shay, Belle Wilburn, Margaret Froggatt, Joan Linford, Mary Lee, Mary Bamford, Kath Norman, Joy Mendham, Pam Simpson, Jean Mendham.

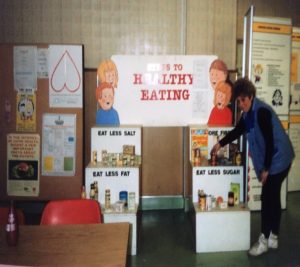

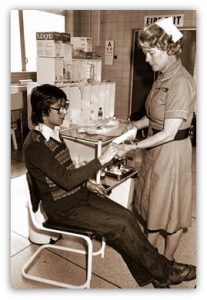

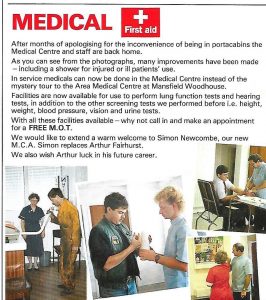

Thoresby Colliery Medical Centre

Sister Marian Foster with medical attendants, Arthur Fairhouse, Haydon Johnson and Neil Wallace medical centre attendants covering a 24-hour shift cycle in 1976.

Sister Marian Foster with medical attendants, Arthur Fairhouse, Haydon Johnson and Neil Wallace medical centre attendants covering a 24-hour shift cycle in 1976.

Hayden Johnson

Sister Sue Bevan, Healthy Eating Campaign

Sister Sue Bevan, Healthy Eating Campaign

Sister Sue Bevan and Trevor Hayward opening the new Medical Centre

Thoresby Record Breakers

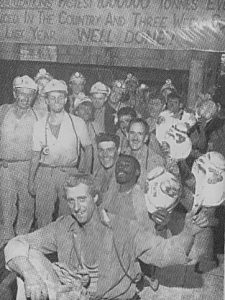

One of the most productive coal mines in Europe in 1951, Thoresby became the first mine in the nationalised coal industry to exceed a million tons output in a year. They failed in only four years during the period 1951-1988 to exceed a million tons production. During 1986/87 the European record of 61.718 tons in one week was produced at Thoresby. In July, 1988, two European records were broken when output soared to 64,453 for the week. The week ending September 23, 1989 two further European records were achieved when 91,040 tons were produced by 1,100 men.

For the year 1988/89 the record output at Thoresby was 2,307,419 tons with 1,231men and a profit of £35 million.

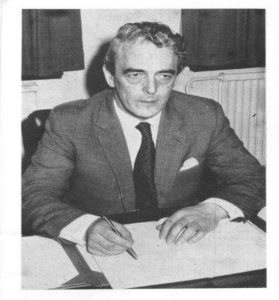

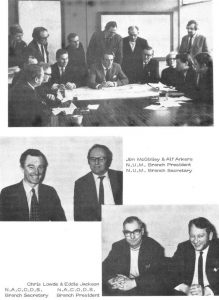

Colliery Managers

Mr C.E Woodward 1926 -1948 Mr I.G.E Leake 1948 -1950

Sam Thorneycroft 1950-1967

Sam Thorneycroft 1950-1967

John Hammond, whose working life was spent at Thoresby Colliery, has a vivid memory of all the names of the officials and his workmates. Sam Thorneycroft was the Manager and he lived at Edwinstowe Lodge, which has since been demolished to make way for the Maid Marian Drive. The Under-manager, Harry Jones, lived opposite Edwinstowe Lodge in one of the Villas which were reserved for colliery officials.

John Hammond, whose working life was spent at Thoresby Colliery, has a vivid memory of all the names of the officials and his workmates. Sam Thorneycroft was the Manager and he lived at Edwinstowe Lodge, which has since been demolished to make way for the Maid Marian Drive. The Under-manager, Harry Jones, lived opposite Edwinstowe Lodge in one of the Villas which were reserved for colliery officials.

John’s first few days at Thoresby were spent with Edie Cole who was the telephonist at the colliery, and one of his duties was to man the exchange during her lunch break.

John, who started work in October, 1952, aged 16, has an impressive recollection of Thoresby’s officers: Frank Wright (Head Surveyor), Jim Draycott (Training Officer), Jack Fell (Safety Officer), Bill Russon (Chief Clerk and Cashier), Fred Kent (Wages’ Clerk), George Nuttall (Compensation Clerk) – the job to which John was to succeed – Sid Maynard (Area Administration Officer), Frank Bennett (Full Weigh), Ken Flecknall (Empty Weigh), Ted Gee (Head Storekeeper). John remembers, during his time in the Wages Office, going by Morley’s Taxi to collect the money from the Westminster Bank at Worksop for both Thoresby and Ollerton Collieries, and a member of the wages staff had the job of collecting the rent from the widows in the village.

He also remembers that Sam Thorneycroft, the Colliery Manager, would often shoot rabbits from his office window.

Bob Anderson

1967 – 1974

Terry Wheatley 1974 – 1984

Management team – David Betts, Cyril Perkins, Brian Wright, Jack Storr, Terry Wheatley, Ken Fidler, Carl King, Keith Raynor

Stan Bryce, Ron Murphy, Mark Lee, Alf Holt, Ken Smith (stood on a box) Ernest Bramley, Kev Moore.

Stan Bryce, Ron Murphy, Mark Lee, Alf Holt, Ken Smith (stood on a box) Ernest Bramley, Kev Moore.

Blacksmiths 1980’s

Dave Edwards

Blacksmiths 2015

Blacksmiths 2015

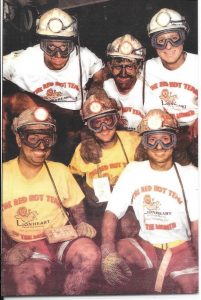

The Red Hot Team

Dean Radford, (Radder) Dave Holmes (Star) Garry Hales, (Gadger) Andy Brooks, (Brooky) John Scrivens, (Scratch) Craig Wath

Dean Radford, (Radder) Dave Holmes (Star) Garry Hales, (Gadger) Andy Brooks, (Brooky) John Scrivens, (Scratch) Craig Wath

Installation of Compressor 1990

Andy Graham, Jim Goodwin, John Eaton, Colin Wyld, Mick Hutchins, Alan Baker, Andy Brentnall, ?

DOSCO

Daily Headgear Inspection 1977

Alan Baker

The Jewel in the Crown Headstocks

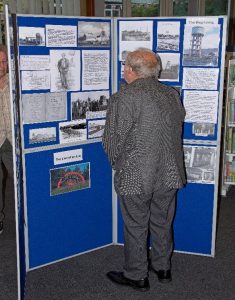

Thoresby Colliery Exhibition – 2015 The End of an Era

On 21st September at Edwinstowe Library many former miners were reunited sharing memories with workmates (including 5 former managers).

On 21st September at Edwinstowe Library many former miners were reunited sharing memories with workmates (including 5 former managers).

Ken Fidler, Bob Hallam, Derek Main, David Betts, Terry Wheatley

The opening of Edwinstowe Historical Society’s exhibition celebrating 100 years of Thoresby Colliery was accompanied by former members of Thoresby Colliery Brass Band led by Stan Lippeatt.

Photographic displays from the sinking of the Colliery and building the colliery village cover many aspects, from work at the coal face and on the surface including the Medical Centre, to St Johns Ambulance, the Pit Trip, the Band, Cricket, Football and Bowls, and the retired miner’s annual tea at the Welfare Hall.

Supported by The Heritage Lottery Fund the exhibition ran until 31st October during normal Library opening hours.

Shirley Moore receiving a painting on behalf of the Edwinstowe Historical Society from David Betts former Colliery Manager.

Thoresby Colliery Benevolent Fund

Former Miners donated £57,000 of their wound-up benevolent fund to a variety of good causes. The fund launched in the 1950s was set up to support members or their dependents, if they were off work, injured or killed in an accident, cash payments were made to them or their families. The beneficiaries of the fund were Berry Hill Park Trust, Beaumont House Community Hospice, Thoresby Retired Miners Party Fund, British Heart Foundation, Lincolnshire and Nottinghamshire Air Ambulance.

Thoresby Colliery 1925 – 2015

The End of an Era

Acknowledgement: Bob Bradley, Acorn Newspaper

Photos: Robin-Stewart Smith. Jay Chapman.

Edwinstowe Physiotherapy Clinic

Opening of 4th Avenue Mineworkers Clinic 1940’s

The End of another Era

On 13 December, 2007, the Edwinstowe Physiotherapy Clinic closed its doors for the last time. The Clinic occupied a block of three houses on Fourth Avenue. In 1929 the building was used as a temporary Institute for the miners, the new Miners’ Institute was opened in 1939, and the building was then converted into the Clinic.

In a recent article for the Acorn, Mr R Cornelius wrote:-Edwinstowe has a clinic because of the vision of the colliery workmen of the late 1930’s. In 1938 discussions took place between the workmen’s representatives of Thoresby and Clipstone Collieries which resulted in the appointment of a Clinic Committee. The first Chairman was C.E Woodward. It later became practice annually for the Chairman to be elected alternately between the workmen’s representative and the Colliery Manager. The longest serving was Mr Sam Thorneycroft.

It was funded by deductions from wages paid at the participating collieries, with Sister Beeley M.C.S.P as physiotherapist throughout the war and after. Through nearly 70 years more than a dozen assistant physiotherapists have contributed to care and relief, with the support from local doctors and other professional people. From 1960 to 1980, Grace Holland provided relief and care with understanding and professional skill. To ensure the waiting was minimal Grace Holland often worked late into the evening.

Most of the people connected with the clinic gave their time generously, not least the office helpers and Secretaries of the Clinic, numbering six since 1939, plus Mrs Joyce Moxon, along with the General Secretary of the of the Nottingham Section of the U.D.M, and three Trustees.

Sadly, the clinic, a totally independent institution, could not win sufficient income to continue its

provision of professional physiotherapy in Edwinstowe. Peter Etchells, Chairman of the Clinic Committee said, “Since the closure of Clipstone Colliery, we have had to rely on grants and donations to keep the Clinic open. I would like to take this opportunity to thank the members of the Clinic Committee for their support over the years. Also, many thanks to Joyce Moxon, the Clinic secretary, who has for 12 years carried out her duties with total commitment and dedication. Her help has been invaluable, especially over the recent difficult years”.

Acorn Newspaper

Mineworkers Clinic Retirement of Sister Beeley Miss Holland Sam Thorneycroft Colliery Manager B Evans Chairman

Edwinstowe Historical Society

Edwinstowe Historical Society