Hoggard – Sylvia Mendham researched her husband’s family history over the last two hundred years and some of it relates to Edwinstowe. Sylvia wrote:

EDWINSTOWE LINKS WITH AMERICA & Family Tree

During the 18th century a William Hoggard came from Treswell, in North Nottinghamshire, to live in Edwinstowe and married a Martha Breedon of Norton Cuckney.

Norton Cuckney Green

Norton Cuckney Green

William was a blacksmith and lived at the back of where Karissma Beauty shop is and where the Sweet shop stands on the High Street today. He and his wife raised a large family and other sons went on to become blacksmiths and the family is reputed to have made the gates of Rufford Abbey. My husband is descended from the Hoggard family and we now live in Edwinstowe, as does his married sister. William’s grandson, James, born in 1823, moved to Lambley near Nottingham. He married Emily an embroiderer.

Rufford Abbey Gates c1950s

One day in 1852, after they had been married for ten years missionaries, from the church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (or Mormons) came and they were eventually baptised into the faith. They dreamed of joining other Mormons in the United States, and in 1854, James set sail across the Atlantic, to prepare a home for Emily and their four children. It was a harrowing voyage for the five hundred passengers, half of whom were Latter Day Saints. The sailing ship, Germanicus, was becalmed for twenty days in an oppressive heat, with food and water supplies running low, and the vessel was grounded for a time in shallow water. The ship eventually arrived in New Orleans, having spent sixty- seven days on the voyage from Liverpool. A steamboat took them to an Island near St Louis, Missouri, where the passengers spent two weeks in quarantine. James worked and saved for a year and then sent for his wife and family.

A Family Sustained by Faith

In the December issue we heard how James Hoggard left his wife and five children in Calverton in April, 1854, with the object of setting up a new home in the New World, among Mormon friends.

James Hoggard Emily Hoggard

Having worked hard for a year in Missouri, James sent for Emily and their children, who then had to endure a hazardous Atlantic crossing in cramped conditions. Emily was ill for much of the way and ten-year-old Mary had to take on her mother’s duties as cook, nurse and baby-minder. A baby, whom James had never seen, died at sea from a sudden illness.

The family first stayed at Burlington, Iowa, Emily taking in sewing and James working on a boat on the Mississippi River, until they had saved enough money to pay for their journey to Utah, the Mormon settlement and their ultimate destination.

It was in March, 1856, that the family, including another baby, set off on the one thousand mile trek to join their pioneering brethren, and they arrived in Salt Lake City after an anxious five months. Films tend to glamorise this journey, showing the migrants travelling in spacious covered wagons drawn by teams of oxen. The truth is that most had to pile their possessions and precious belongings on to handcarts.

Yet another child, four-year-old James, met an early death on this long march and, as Sylvia Mendham vividly relates: “It is hard to imagine the hardships and heartache the family endured, but it makes one understand a little of their strong belief and determination to reach their intended goal.”

Other, later, wagon trains were caught in snowstorms and some travellers died, while many lost limbs through frostbite or came near to starvation before being relieved by supplies sent out from Salt Lake City.

On their arrival in the settlement of American Fork, the Hoggard family began to earn their own living, James cutting hay and corn and Emily and her children gleaning. The grain, which they gathered, was eaten or ground into flour, sufficient to see them through the winter.

Mormon settlement of American Fork in Utah.

By the time they had settled in their permanent American home only three of their offspring had survived the perilous journey. They built their own humble home, in which seven more children were born, although one died at birth. (The house still stands today).

Their family was raised by dint of hard work. James always rose by 3am every morning and worked long hours on the land but was always ready to help his neighbours. Emily learned to braid straw hats which had a special appeal to all who worked in the fields, especially in the oppressive summer heat.

James discovered that he had the gift of healing and he was often asked to heal cuts and more serious wounds, as well as to set bones. He was able to apply this God-given talent to curing animals and he was known to spend hours with a sick horse or cow.

He was the first to be appointed Head Watermaster at American Fork, a post which he held for twenty-one years. He supported every co-operative project in the community, which gradually became prosperous. He and Emily opened their doors to all new arrivals, until they were settled, and helped them to find work.

They both loved music and dancing and they invited all in the settlement to their house to celebrate every New Year’s Day and Night.

All went well until James was suddenly taken ill while working with one of his daughters in a field. He never recovered and died shortly after his 60th birthday. Emily lived on for another thirteen years, supported by the love of her nine surviving children, fifty-six grandchildren and twenty-six great-grandchildren, but she never really came to terms with the loss of her husband who had been her strength and stay.

Sylvia has twice visited American Fork where she was welcomed as one of the Hoggard family.

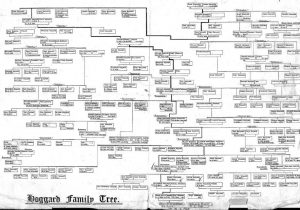

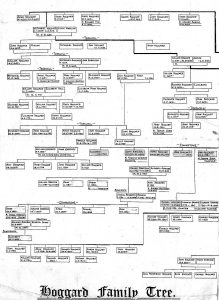

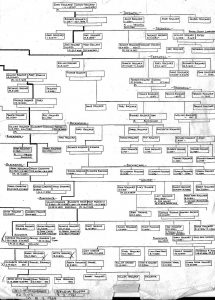

Hoggard Family Tree

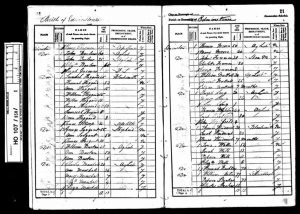

Edwinstowe Census 1841 – Hoggard resident on Town Street (High Street)

Edwinstowe Historical Society

Edwinstowe Historical Society