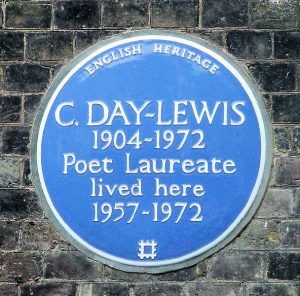

Poet Laureate 1967

Cecil Day-Lewis, born in 1904, was the son of Frank Cecil Day-Lewis, a Church of Ireland curate. His father moved to Ealing where Cecil’s mother died when he was 4 years old. Her sister became his surrogate mother for 12 years “with a devotion few other women could have equalled”. She aroused in Cecil an interest in music and singing arias from Handel’s Messiah and popular songs of the time. Cecil could pick up a melody and had a mellifluous, melodious voice.

Cecil Day-Lewis, born in 1904, was the son of Frank Cecil Day-Lewis, a Church of Ireland curate. His father moved to Ealing where Cecil’s mother died when he was 4 years old. Her sister became his surrogate mother for 12 years “with a devotion few other women could have equalled”. She aroused in Cecil an interest in music and singing arias from Handel’s Messiah and popular songs of the time. Cecil could pick up a melody and had a mellifluous, melodious voice.

Cecil was 14 when his father was appointed Vicar of Edwinstowe. His parish included Budby, Perlethorpe, Carburton and the neighbouring village of Clipstone, whose colliery was operating by 1922 (after the army training camp closed). “During the holidays, we were together a great deal. I used to drive him everywhere in the car- a practice that taught me patience, if nothing else. My father was king of back-seat drivers, barking out “Horn!” whenever we approached a crossroads and “Change down now!” on the slightest acclivity. Often, I had to wait for half an hour outside some parishioner’s house or for hours in a garage while my father who had a probably justified mistrust of motor mechanics, stood over them at their work of repairing our rickety second-hand vehicles…My father, having no capital, ran into debt furnishing the vicarage and buying a second-hand Humberette, a devilish little two-cylinder car that used to backfire like the kick of a mule when he tried to start it…the Humberette was a bad buy, and only the first of several forays into the second-hand car market. ” C. Day-Lewis The Buried Day

Cecil reminisced about Edwinstowe: “When we first went there, the black-faced miners cycling home from work with their snap-tins bumping at their sides were outnumbered by the farm labourers whom they passed in the village street, exchanging a curt Midland ‘How-do?’ Twenty years later, almost every man would be working in the pits. Soon the new housing estates were to obliterate the contours of the fields, which, as a boy, I had seen tossing with wheat or barley.” “So, then my adolescence smouldered away, acrid as the reek of the slag-heaps which tainted the air, an odour of harsh sterility that grew ever more pervasive as new pits were opened in the neighbourhood. Grime from colliery workings, borne on the wind from Mansfield or Clipstone, thickened on our rockery and lawn and rambler roses, smirching one’s tennis flannels when they touched it, while every holiday I was reminded of that “other nation” and the dangerous war they waged, hearing of its casualties –men injured by falls of roof, maimed by runaway tubs, killed by an explosion or the cage dropping out of control from a pithead–accidents some of which, for all I knew, had occurred deep below my feet as I sat in the sunny rock garden reading Swinburne or the early Yeats. When an injured man was a parishioner of my father’s he often went into hospital …and sat by the bedside so that the first face the patient saw on recovering consciousness should be a familiar one…Remote though the miners’ lives were from me, it is at Edwinstowe that my social conscience was born.” He recalls that his father’s stipend of £600 per annum came largely from Earl Manvers, the titled patron of the living, beneath whose land the coal had been found.

An all-round games player, at prep. school he was captain of football and cricket and was a formidable Rugby player at Sherborne. Father and son went to Trent Bridge and particularly admired Harold Larwood’s bowling. They played tennis a lot and golf on the Duke of Portland’s private course at Welbeck; “or we punted a rugger ball to and fro across the meadow which divided the vicarage from the church-it became a ritual that on the afternoon of Christmas Day we should work off our heavy lunch thus.”

While his father was army chaplain, Cecil had learned to ride a horse. He was sometimes invited to one of the big houses in the Dukeries, but he felt at a disadvantage. Cecil claimed to have been “socially insulated” in Edwinstowe, but residents remember that his tennis partners included local girls Hilda Digby, Annie Parnell and Edith Woodhead (Coles). His father was very class-conscious. Cecil was not allowed to join the church choir or the Boy Scouts because the boys were not of his class.

In the 1990’s, Edwinstowe resident, Dennis Wood, collected memories of the Day-Lewis family. As a schoolboy, Cecil loved to challenge older boys to a friendly, good-natured bout of wrestling and chase about ‘releasing the excess energy.’ A fun-loving youth, he put a high value on friendship, but had few intimate friends among the Edwinstowe boys.

ELH 1597 Old Vicarage with Revd Frank Day-Lewis c1926

One of the choirboys said: The Vicar “was the traditional disciplinarian, aloof, conscious of his role and position in society”. [Hardly surprising when in London he’d numbered the Lord Mayor among his congregation!] He assisted the choirmaster and had a firm musical knowledge. His code of behaviour for young people was strictly enforced, but one elderly lady found him kindly when she was a girl. He questioned the Sunday School children on the Collect of the Day and during visits to the church school tested the children’s understanding of the Scriptures.

However, Margaret Woodhead recalled that during the sinking of the new Thoresby Colliery, water-ingress caused serious problems. Meeting her father, one of the ‘sinkers’, Reverend Day-Lewis demanded an explanation why he had missed singing in the choir the previous Sunday and angrily issued an unsympathetic ultimatum.

Reverend Day-Lewis had enjoyed being an army chaplain during the 1914-18 war, although he never saw active service. In 1921, he had the original altar stone restored to the Lady Chapel in St. Mary’s Church which became a War Memorial housing a board on which were inscribed the names of the dead. (The chapel altar-rail was later dedicated to his memory.) A stone War Memorial cross was also erected at the cross-roads. His sonorous tones could be clearly heard, not only by the weekly congregation, but also by the hundreds of people assembled near the War Memorial on Armistice Day.

Reverend Day-Lewis had enjoyed being an army chaplain during the 1914-18 war, although he never saw active service. In 1921, he had the original altar stone restored to the Lady Chapel in St. Mary’s Church which became a War Memorial housing a board on which were inscribed the names of the dead. (The chapel altar-rail was later dedicated to his memory.) A stone War Memorial cross was also erected at the cross-roads. His sonorous tones could be clearly heard, not only by the weekly congregation, but also by the hundreds of people assembled near the War Memorial on Armistice Day.

http://southwellchurches.nottingham.ac.uk/edwinstowe/hwarmem.php

Armistice Day Service Edwinstowe 11th Nov 1929

Whilst Cecil was at Sherborne School in 1921, Frank married a well-connected woman with her own income, Margaret Kathleen Maud (aka Mamie) Wilkinson. Cecil despised his step-mother’s Victorian values and bourgeois attitudes. She dressed the house-maids in frilly aprons and locked away any items of value. “House-proud and possessive, Mamie kept every drawer and cupboard locked. If the cook needed a pinch of salt, a cupboard had to be unlocked…the inefficiency of this arrangement used to madden my father and myself, to say nothing of our domestic staff.” Mamie liked rich food, including lobster on Fridays. She showed her devotion to her husband and the under-exercised, large Labradors or Airdedales she kept as pets, by overfeeding them until their health suffered. She would constantly call the dogs to her and drag them round the house on a lead. One or two died prematurely; but nothing would convince her that her treatment was largely to blame for their decline.

Cecil’s relationship with his father deteriorated, shattering the father-son bond, which had been so full of joy. His father would often lapse into sulks and rages and could never express contrition. Cecil sang in the choir and read lessons at St. Mary’s, but his disenchantment with his father kept him away from Holy Communion.

Cecil won a scholarship to Wadham College. In the intellectual climate of Oxford, Cecil’s wits quickened and flowered and his undoubted charisma came to the fore, endearing him to many of his companions such as John Betjeman, Nancy Mitford, David Cecil and Rex Warner. From 1925 he published his poems some of which were praised by Robert Graves.

After his final exam in Classics, Cecil taught for a year at Summer Fields, Preparatory School and in 1928, he married Mary King, the daughter of one of his masters at Sherborne School.

In 1930, he started writing detective novels under the pseudonym of Nicholas Blake – in A Penknife in My Heart one of the characters is called Edwin Stowe!

Mary and Cecil would alternate their holidays between Edwinstowe Vicarage and Mary King’s family home. Cecil paid little attention when his 60 year old father wrote to tell him that his health had deteriorated. It came as a shock when Frank died of a heart-attack in the middle of the night on July 29th, 1937. Although the funeral was held at St Mary’s Church, after the service the coffin “was placed in a motor hearse and conveyed half-way across England to Bath; where my step-mother wished to lay it in her family tomb.” According to Jill Day-Lewis, Cecil’s second wife (to whom this author wrote some years ago, hoping for pictures of the Vicarage at this period), Mamie took it on herself to consign the family photographs to the bonfire.

Cecil excelled as a translator of Virgil, his translation of the Aeneid was broadcast by the BBC. He wrote over twenty Nicholas Blake detective novels, published several volumes of poetry and became Poet-Laureate on New Year’s Day 1967. He died in 1972 and is buried near Thomas Hardy in Stinsford churchyard.

Cecil excelled as a translator of Virgil, his translation of the Aeneid was broadcast by the BBC. He wrote over twenty Nicholas Blake detective novels, published several volumes of poetry and became Poet-Laureate on New Year’s Day 1967. He died in 1972 and is buried near Thomas Hardy in Stinsford churchyard.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cecil_Day-Lewis

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cecil_Day-Lewis

Based on Dennis Wood’s research. Also The Buried Day C. Day-Lewis Chatto & Windus 1960; C. Day-Lewis a Life Peter Stanford, Continuum 2007

Edwinstowe Historical Society

Edwinstowe Historical Society